How did your journey into wildlife photography start, and what drew you to this genre?

Nobody knew me before 2015. I was just a regular guy, I took my kids to school, went to work, and lived an ordinary life. But everything changed when I picked up a camera and started posting simple shots of birds and garden life on Instagram. That small step opened a new door for me, one I never imagined I’d walk through.

I grew up in Kuwait, a country often dismissed as dry and lifeless. But once I began exploring it through the lens, I discovered a world I never knew existed. I had no idea we had such rich biodiversity. I didn’t know we had owls nesting here, Little Owls and Pharaoh Eagle Owls. I didn’t know we had migratory raptors like eagles, vultures, and buzzards passing through in the hundreds. I had no clue that Sand Cats still roamed our deserts, or that Lesser Crested Terns and White-cheeked Terns nested on Kubbar Island.

Joining the Bird Monitoring and Protection Team at the Kuwait Environment Protection Society was a turning point. They took me to places I’d never seen before, taught me how to read the land, anticipate behavior, and truly observe. I’d finish work and head straight to the desert, eat dinner out there, and return late at night. It became my second life and eventually, my first.

One early memory stays with me: the first time I saw two Griffon vultures in the Kuwaiti desert. They were massive. Mohammad Khorshed and I got out of the car barefoot, afraid the sound of our shoes on the gravel would scare them off. We crawled on our stomachs like soldiers until we were close enough to photograph them. That was the moment I realized I was completely drawn in not just by the image, but by the experience.

Wildlife photography hooked me because it is raw, unscripted, and deeply emotional. Nothing is posed. Every moment is real and every image is earned. That’s what keeps me going.

What does wildlife photography mean to you personally?

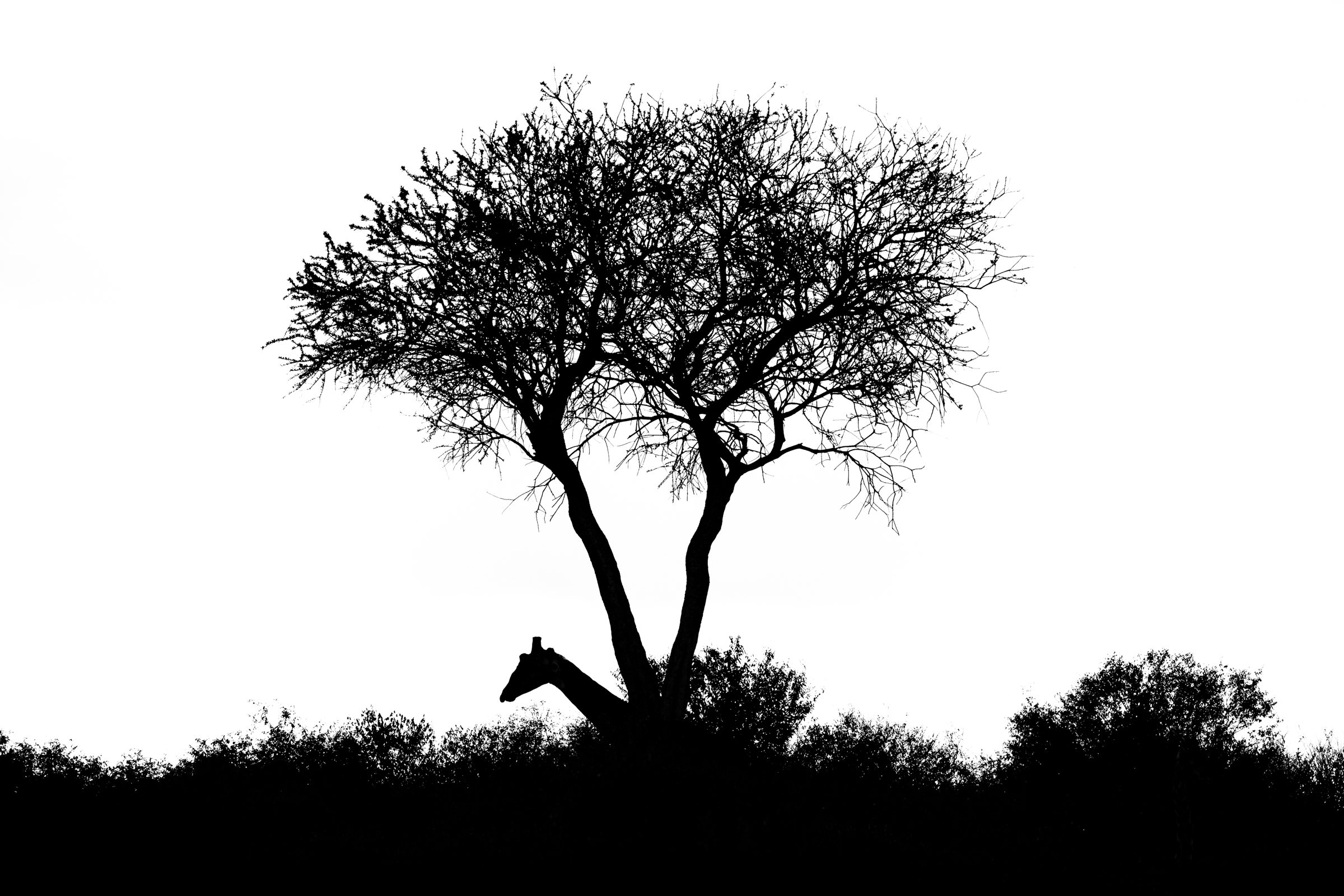

Wildlife photography is not just something I do, it’s who I am now. It’s a dialogue with nature, a way to connect with something much bigger than myself. I often say it’s like music: when a violinist plays a melody, he’s expressing something internal, something raw and whether people understand it or not doesn’t matter. That’s how I feel when I create images, especially with intentional camera movement or slow shutter. It’s not about the perfect shot. It’s about honesty, emotion, and offering a piece of myself to the world quietly, but fully.

And the most meaningful part? When my daughters once came home from school saying, “We read about you in the newspaper”, and proudly showed my work to their friends. That meant more than any award I’ve ever received.

Many of your images carry a powerful sense of mood and atmosphere. How do you achieve that in the field?

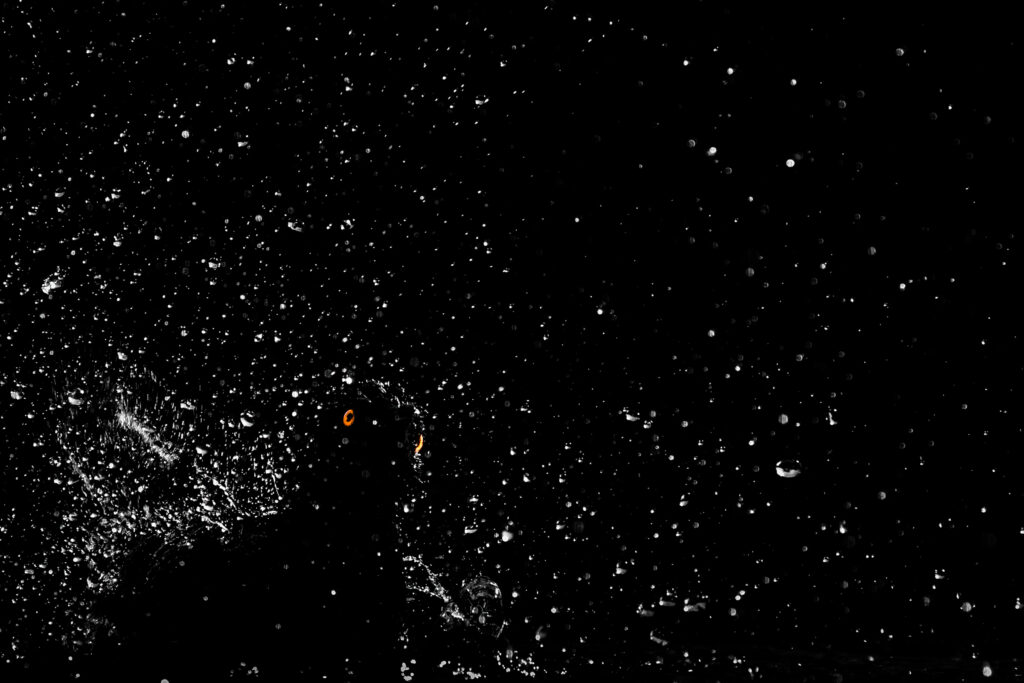

Mood in photography is like breath in music it gives life to stillness. I often use slow shutter techniques and intentional camera movement (ICM) to add motion and emotion to my frames. I want the viewer to feel that the animal is doing something not just standing there. I’m not afraid to blur the scene, to create mystery, to transform the image into something expressive.

To me, this style is like drawing with light and energy. It’s abstract, it has no rules and that’s exactly what makes it so intimate. Every image becomes a personal sketch of how I felt in that moment.

Can you walk us through one of your most memorable shoots and what made it unforgettable?

I’ve had many unforgettable moments, but my expedition to Iceland stands apart. It took six months to plan. I prepared meticulously, buying all my gear from outside Kuwait to endure the snow. But when I landed, the airline lost my luggage. I had no proper winter clothing.

The other photographers kindly lent me what they could, but I was still freezing, my toes went numb, I couldn’t crawl on the ground for long, and I had to stay close to the hut. But somehow, that limitation gave me a different perspective. I took shots that no one else did from closer range, more minimal, more emotional.

What made it truly unforgettable wasn’t just the images it was the warmth I received from the other photographers, and the humbling beauty of the landscape. Iceland felt like a dream. Even in discomfort, I was overawed.

Do you plan your shots in advance or let the moment guide you?

I do my homework, I research animal behavior, light conditions, the terrain. But once I am in the field, I surrender to the moment. Animals don’t follow scripts, and neither should we. Some of my best images happened when I let go of expectations and simply listened to the wind, the light, the rhythm of the wild. I trust my instinct more than any plan.

How do you balance the artistic and ethical aspects of wildlife photography?

Ethics come before art. Always.

No image is worth distressing an animal. I never bait, lure, or provoke, no matter how tempting the opportunity may seem. Sometimes the scene pulls you in, your heart races, your instincts beg you to press the shutter. But that’s exactly when you need to pause, breathe, and put the animal first.

We must remember we are guests in their world. I’ve learned to read subtle shifts in behavior, posture, movement, even silence. If I sense discomfort, I step back. A photograph taken without respect will always carry that absence of trust. And other photographers will see it, you can feel stress in a frame, even when nothing is moving.

For me, true beauty lies in honesty. The most powerful images come when the animal is at ease, when the moment unfolds naturally, and the photographer is simply allowed to witness.

As John Muir once wrote, “In every walk with nature one receives far more than he seeks.” That’s the spirit I try to carry not to take from nature, but to receive what it offers, with humility and care.

What challenges have you faced while photographing in extreme environments?

Kuwait is no easy place for wildlife photography; temperatures can reach 56°C. It’s like standing in an oven. Dust storms are frequent and they can destroy your camera sensor if you’re not careful.

In contrast, in Mongolia and Iceland, I’ve faced temperatures as low as -35°C. I’ve had frostbite in my fingers, frozen camera batteries, lost luggage, and days of complete physical exhaustion. But through it all, I’ve learned that discomfort is part of the process. You adapt. You adjust. And in the struggle, you find something pure.

How do you prepare for a wildlife expedition mentally, physically, and technically?

Mentally, I prepare by letting go of expectations. Wildlife photography teaches you to be present to observe more than you act. You can’t control nature, so I focus instead on building patience and staying open to whatever the wild chooses to offer.

Physically, I train for endurance. The body has to carry heavy gear, hike long distances, crawl, and wait for hours often in extreme conditions. Before my Mongolia expedition, I trained for three months just to be ready to hike the mountains. And still, it was hard. The cold, the altitude, and the wind were unlike anything I’d faced before. It reminded me that no amount of training truly prepares you, only the wild can do that.

Technically, I make sure every piece of gear is tested, cleaned, and ready. I pack backups, extra batteries, and think through worst-case scenarios. I also set up my camera customizations in advance. I assign specific functions to buttons so I can adapt quickly, even with gloves on. I want to be able to change settings in a blink, without taking my eye off the moment.

Still, no matter how prepared I am, nature always finds a way to surprise me and that unpredictability is part of the magic.

What’s the longest you’ve waited for a shot, and was it worth it?

One of my most meaningful experiences was spending nearly three months with a family of Arabian red foxes that had chosen to raise their kits near Kuwait City. something incredibly rare, as these foxes usually breed deep in the desert.

I visited their den four to five days a week, sitting for hours after sunset. At first, I kept a distance of about 20 meters, but over time, they grew used to me. Eventually, two of the kits were so comfortable they began licking my camera and feet, a level of trust that moved me deeply.

The final image – a young fox framed by the colorful glow of city lights came after weeks of waiting. I used two small continuous lights and patiently waited for the moment they’d return to dig up food the mother had hidden. That photo wasn’t just a result of technical planning it was built on patience, presence, and quiet respect.

And yes, it was worth every single second.

What fascinates you about owls, and how do you photograph them so intimately?

Owls are silent spirits elusive, graceful, and deeply mysterious. In Kuwait, we have four species, and I’ve spent years observing them. They don’t reveal themselves easily, but once they accept your presence, they offer moments of rare intimacy.

The Pharaoh Eagle Owl, for example, roosts in rocky crevices or caves by day and becomes active after sunset. With extraordinary night vision and a unique third eyelid, the nictitating membrane, they’re perfectly adapted for nocturnal hunting. These details fascinate me, but it’s their presence that moves me most.

Photographing owls requires trust. You learn their rhythms, stay quiet, return often. Over time, they stop seeing you as a threat and start allowing you into their world. That quiet bond is what I aim to capture. Every image is a conversation without words.

What role has social media, especially Instagram, played in your journey?

Instagram was the spark. It’s where I first began sharing my work in 2014, and the encouragement I received gave me the confidence to pursue wildlife photography more seriously. Through the platform, I connected with a global audience and became part of a larger conversation about nature, storytelling, and conservation.

It was also where I discovered the work of incredibly talented photographers, their images inspired me to push my own limits. I followed them, studied their work, learned about the places they photographed, and the competitions they entered.

But no matter how powerful social media is, I always remind myself: the image must come first. Likes come and go, but a meaningful photograph will always find its place.

What gear do you currently use, and why?

I shoot with two Canon EOS R3 bodies, paired with lenses like the Canon RF 400mm f/2.8, the RF 100–500mm f/4.5–7.1L IS USM, and wide-angle lenses for creative and ground-level perspectives. I also use ND filters to control shutter speed in daylight especially for my motion-based work.

My favorite combo what I call the “beast combination” is the R3 with the RF 100–500mm. It’s lightweight, versatile, and fast. I don’t need a tripod, and I’m ready for any situation, whether I’m crawling in sand or reacting to sudden animal movement.

For me, gear must be reliable, responsive, and able to withstand extreme conditions. But ultimately, gear is just a tool. Vision comes first.

How have international awards impacted your work?

Awards are affirmations, they tell you that your vision, your way of seeing the world, matters. They’ve brought my work into the spotlight, giving me exposure I never actively sought but one that came as part of the journey. Suddenly, people and organizations I’d once admired were reaching out to me.

Thanks to the recognition from major competitions, I was invited to speak at international photography festivals like GDT in Germany and Xposure in Sharjah. I also had the honor of becoming a Canon Ambassador for Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa something I never imagined when I first picked up a camera.

These awards opened doors, brought credibility, and helped me reach beyond borders. But they didn’t change why I photograph. I still shoot for the love of nature, for the story, for the feeling. And the greatest reward? It’s when my children look at my work and say, “That’s my dad.” That moment outweighs any medal.

I was just a regular man, unknown outside my circle of family and friends. Through hard work and devotion, I now stand on the stages of the most prestigious competitions in the world. That transformation means more to me than any trophy ever could.

How can wildlife photography contribute to conservation and awareness?

A powerful image can touch the heart before the mind has time to speak. It stirs empathy and empathy leads to action. When people feel connected to a species, they begin to care. And when they care, they protect.

Wildlife photography makes the unseen visible and often unforgettable. It has the power to turn curiosity into concern, and concern into change.

Personally, I use my work to support conservation efforts whenever I can. For example, when the United Nations approached me for images of the Pharaoh Eagle Owl for an awareness campaign, I provided them for free. For me, that’s not a transaction it’s a responsibility. If an image can play even a small role in protecting a species or preserving its habitat, then it has served its highest purpose.

What’s your workflow like after a trip?

The first thing I do is back everything up always in two separate storage locations. Once that’s done, I take some time to rest and reflect before jumping into the editing process.

When I’m ready, I go through every single image one by one, rating them with stars. Some photos are selected for daily Instagram posts, others I set aside the, ones I like but need to revisit with fresh eyes. And of course, there are images I set apart specifically for competitions.

I do all my post-processing in Lightroom, applying only minimal adjustments. I focus on enhancing the light, color, and mood without changing the essence of the moment.

For me, post-processing isn’t about creating perfection it’s about preserving the soul of the scene, exactly as I felt it in the wild.

Have you noticed changes in how wildlife responds to human presence?

Yes. Some species are becoming bolder like foxes near urban areas. Others are disappearing into deeper isolation. Wildlife is adapting, but it’s not always a good sign. Their behavior reflects the pressure we’re placing on them. We must be aware, and act with responsibility and humility.

What advice would you give to aspiring wildlife photographers?

Start with what you have. Borrow gear, rent it, learn with what’s available. Don’t wait for perfection. Just start.

And most importantly don’t imitate. Find your own voice. Talk to the people who inspire you. Be humble. Work hard. And don’t expect instant results.

Recognition takes time. Just love the process, and it will love you back.

What species or place is still on your bucket list, and why?

There’s a long list of species I’d love to photograph I think every wildlife photographer dreams of capturing as many animals as possible in their lifetime.

For me, one of my personal goals is to photograph all the fox species in the world. I’ve spent years with Arabian red foxes, and now I find myself drawn to their cousins in colder, more remote landscapes places fully blanketed in snow, where silence and solitude shape everything.

Lately, I’ve been gravitating toward the far north, places of profound isolation, untouched by human presence. It’s not just a photographic goal; it’s a spiritual one. To witness that kind of purity and to earn a moment within it would be an honor.

What’s next for you?

I’m currently working on a visual series titled The Art of Motion, a project where I combine wildlife behavior with abstract storytelling, using slow shutter and intentional movement to explore emotion through motion.

I’m also developing Arabic-language educational content for aspiring photographers. There’s a real need for accessible, high-quality resources in our language and I want to help bridge that gap and share this passion with a wider audience across the region.

And as always, I’m chasing the next moment, one that can’t be planned, only felt.