A sudden cry and a noisy flutter of wings broke the quiet that surrounded us.

A party of peahens had taken off from near the crest of the hills just ahead of us, squawking in alarm, outlining themselves against the clear skies behind them.

Alert, hands gripping our cameras we were focused on the spot where the birds had suddenly flown from to see what could have spooked them.

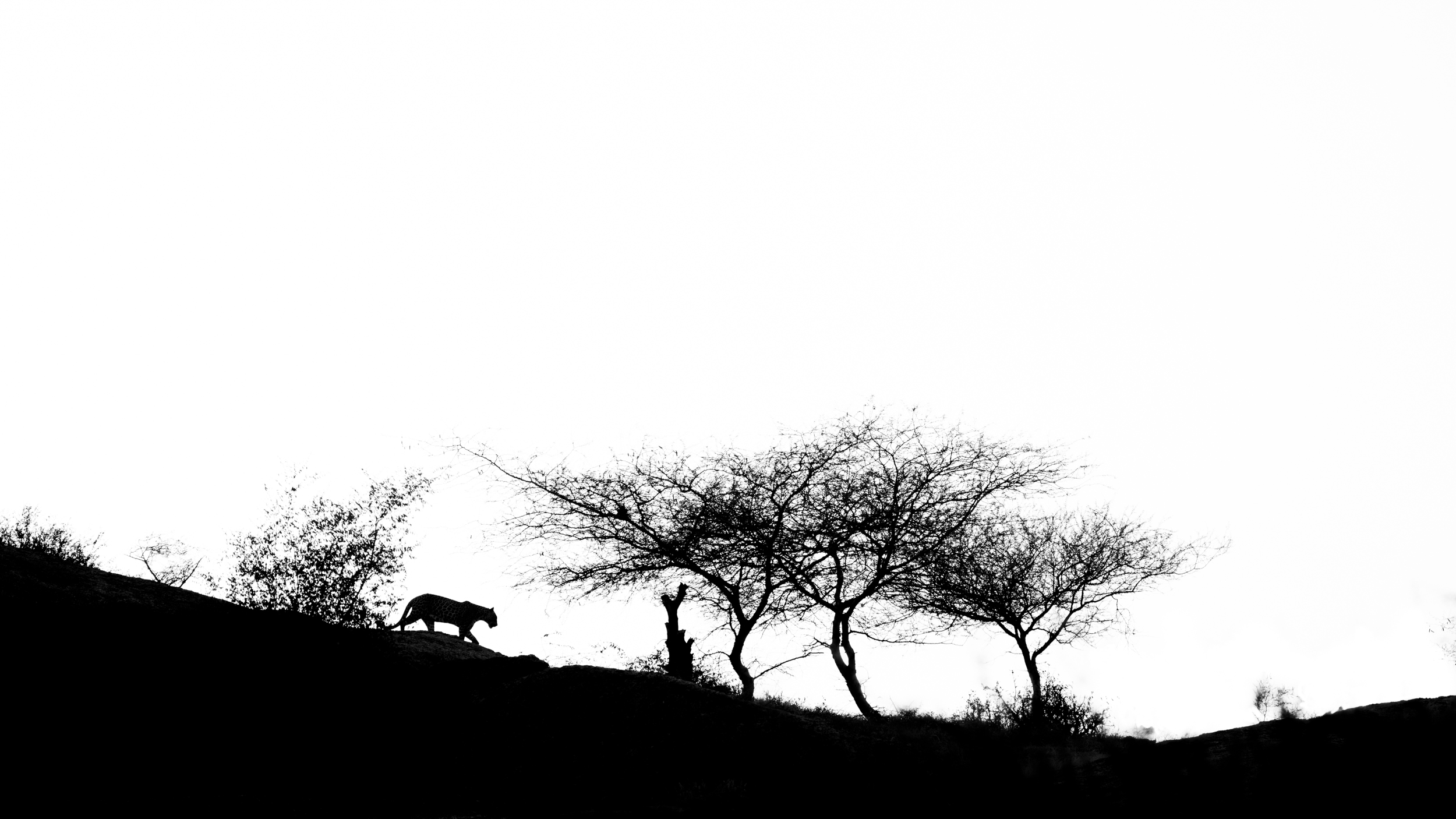

Sure enough, a moment later, we could discern movement and soon amid the undulating sea of rock and the odd cactus, the head of a leopard came into clear view, carefully scanning the surroundings.

Slowly, with caution evident in every step, it began its descent, pausing every few seconds and looking around.

He, for it was a young male, was in foreign territory.

This is the territory of a much older male. He is an intruder.

What is happening?

Bera.

It was a small and relatively obscure village till some time back, in the eastern part of Rajasthan, about 125 kms from Udaipur. In the recent past, it has become fairly popular amongst wildlife enthusiasts.

Bera is one of those rare places where reportedly there is minimal man-animal conflict. While that in itself is interesting, what makes Bera truly stand out is something different. It is one of the few places in India where a decision was taken to push commercial interests back and let nature be.

That story began in 2013.

While on a small break at Bera, Shatrunjay Pratap Singh heard a few blasts that made him curious. A few quick enquiries revealed to him that the Government had given licenses for mining to be done in the area. Nineteen of them and many more in the pipeline.

Bera and the other nearby villages were around this cluster of rocky hills. Volcanic rock. Baked by the sun, curved and twisted by wind and the elements over centuries, it was the perfect source for granite and other products.

Bera was also a home for leopards. They reigned in this area.

If the mining continued, the hills will be destroyed, and along with it, the homes of the leopards.

Shatrunjay felt strongly about it and decided to fight for the leopards.

A new battle began in Rajasthan, very different from what this famed land was known for in the years gone by, but which required no less valour and shrewdness.

He was nervous. He paused repeatedly, tail twitching agitatedly, he sniffed around for any recent signs of the older male and, occasionally turned his bright eyes on us.

He might have been wary, but he knew exactly where he was going.

He was headed straight for the caves right in front of us where we knew a female leopard was resting. To make matters more interesting, we knew that her two sub adult cubs were with her.

We wondered what will play out right in front of our eyes

Shatrunjay made himself more comfortable as he began relating a tale that he would undoubtedly have told countless times earlier.

He filed a case in the courts asking for the licenses to be revoked.

It would not have been an easy battle by any means. Fighting any government isn’t easy. Plus, there definitely would have been the pushback from the deep pockets of the mining companies.

On top of everything, his father-in-law was a Minister in the Government.

However, more than the actual legal battle in the courts, it is the story of how the people themselves were mobilised and sprang up to support his cause that is enthralling.

There was a long, flat piece of rock right at the mouth of the cave.

The young intruder, had made his way to this flat piece of rock. If the wariness in his approach thus far was fascinating to watch, his extreme caution now was even more captivating.

He constantly sniffed around, walking to and fro the entire length of the flat rock. Occasionally, it seemed as if he decided to give up and retreat. But, the instinct to mate was overpowering.

Finally, it seemed to summon all its courage and, I imagined, with a deep breath, vanished into the dark corners of the cave.

The Rabaris are a tribe mostly found in the Northwestern parts of India, who used to completely nomadic but have now mostly settled down. It could be their nomadic nature that explains the meaning of the word Rabari – outsiders.

It is believed that they migrated to India from Iran, through Afghanistan more than a thousand years ago but as is the case with almost every theory, there is a counter theory here too.

The interesting bit that has relevance to the conservation fight is a lovely belief that the Rabaris have about their origin.

The story goes that the Goddess Parvati moulded a camel from the dirt that was collected as she wiped off the sweat and dust off Lord Shiva’s face as he meditated. She gave it life (there is another story that says Lord Shiva created a camel to keep her amused) but the little camel kept running away and Lord Shiva created the first Rabari to mind it.

For the Rabaris, Lord Shiva is an important deity

While the case was debated and fought in the Assembly and the courts, Shatrunjay was increasingly spending more time at Bera. (He later built this lovely little place, where I was staying: https://www.berasafarilodge.com )

A small shrine stood midway up one of the hills which was looked after by a sadhu who seldom, if ever, left the hills to come down to the villages. Food was brought to him by any of the villages around.

Shatrunjay used to spend a lot of time chatting with him in the temple and once, while he was there, he noticed one of those ubiquitous calendars having an image of Lord Shiva. He noticed that the god sat on a piece of tiger skin and that a leopard skin covered him.

He turned to the sadhu and posed a simple question. Clearly, the leopard was dear to their God, but despite that why is it that the Rabaris are not concerned about the mining that will destroy the homes of the very creature that was sacred to their God?

The sadhu pondered over the question for a few minutes and decided to act.

The villages were roused up. People equate to votes. Entire villages would mean a lot of votes. And votes matter to the politicians.

That changed the narrative and soon history was made.

We waited. And waited.

There was no sound, no sign of the drama that might have been happening inside the cave. A female with her two sub adults and an eager young intruder.

We will never know.

Almost half an hour later we heard a flurry of activity behind the caves and we could see the two sub adults scurrying away with the peahens flying above them to ensure that they were leaving.

The intriguing stories that happen around us.

There has been no reported instance of leopards attacking any human in Bera.

Rabaris also didn’t seem to mind the fact that the leopards regularly snatch their goats away. That, usually, is the start of the man-animal conflict.

Shatrunjay, explained the rationale behind that. First of all, the Rabaris believe that if a leopard takes away their goat, it should be considered as an offering to their God.

Secondly, the Rabaris get compensation from the Government for the loss of any animal to the leopard attack. With that compensation, they could buy themselves a female goat which will naturally provide them with goat kids soon.

You give an offering to God, you will get rewarded by your God in multiples.

Of course, it doesn’t always work so smoothly. We heard stories of how the Rabaris run after the leopards, sometimes even into the dark corners of the rocky hillsides to get their goat back. What is important is that they hold no rancour towards the animal for doing what is natural to it.

A little later, we were still digesting all the drama that had happened in front of us, both in plain sight and hidden within the dark corners of the cave. A group of young boys walked past us.

There were two leopards nearby and even if the boys didn’t know about that, they should be aware of the fact that there would be leopards in this area.

Of course, they knew. They were simply not bothered about it.

Bera is a wonderful story of how conservation can work. And how tourism can help. The impact of tourism was evident everywhere. Numerous places to stay, from resorts to homestays, have sprung up all around the villages. Many of the villagers work as trackers and naturally, shops catering to the needs of the tourists thrive.

Economically, they were benefiting from the tourism. Most of the Rabaris continued with their traditional work. Herds still set out to graze. Peacocks still call loudly from the fields.

And the leopards continue to rule the hills.